Don’t forget to visit Amazon and get one, two or several of my books. I have books for cooks, photographers, the oddly-humored, English-learners and more!

This post was originally published on April 28, 2013 and updated on March 10, 2020.

I actually had this particular blog post scheduled for my last installment, but a last-minute invitation to the Heckenwirtschaft changed all that. But here’s a photo I shot last Sunday morning of the local marching band parading down the street once again in front of my apartment. I think it was First Communion at the church or something. But spring is here and the weather is getting warmer, so I know I’ll be hearing that oompah music pretty often til fall.

In addition, this year is the 1000-year anniversary of this little village, so I’m sure they have extra fests planned this year. And I’m also sure you’ll be seeing photos of all the goings-on.

Other than that, I have very few photos to show you this week. However, I thought I would give you glimpse into what it’s like to teach English as a Second Language (ESL) in a foreign country. That’s how I pay most of my bills here in Germany, with a little pocket change coming from freelance articles for online magazines.

Teaching English to non-native speakers has got to be one of the most fun jobs I’ve ever had. I’ve been fortunate to acquire a freelance work permit, which means I can provide instruction for any school I want, as opposed to being an employee at one school, and I can also take on private students.

I’m further blessed that I’ve hooked up with a great school called SprachInstitut Treffpunkt here in Bamberg. I’ve made a ton of money through them teaching people via Skype, which suits me because I don’t even have to leave home for most of my lessons. However, I do teach students on site at the school from time to time and the facilities there are great, as well as the management.

In addition, I currently am working a contract I landed with the US Army to teach English to soldiers’ family members on the local base. There I have students from all over the world, but mostly from Central and South America.

On the other hand, I teach for a couple of other language schools here and there and usually they require me to travel to companies to provide instruction. I don’t mind telling you that I don’t like to have to go on-site, but I enjoy the teaching as much as via Skype. Maybe more.

You can imagine that the dynamics of teaching on-site vs. teaching online are hugely different. It also makes a difference whether the lessons are for business English or general, conversational English. I teach business English in most instances (thank you America for being the global business leader and for inventing computers and the internet, which means anyone in business or using a computer online needs English).

For my lessons on the Army base, though, it’s strictly conversational and tends to be more of a social hour for the students, many of whom have kids and whose husbands are deployed to Afghanistan. This means we can do practically anything we want, so I incorporate show-and-tell, pop music song lyrics, movies and fiction into those classes. What fun we have! In fact, some of the students and I went sightseeing in Bamberg last week. I’ll be sorry when the base closes next year and I will no longer have my group there!

Today I want to take you through a lesson I had recently with a group of managers at Telekom, the German phone company. You can compare it to Verizon or AT&T in the States. The location I go to every Thursday morning is an IT center that services trouble tickets on internet and phone line infrastructure. My students in this particular scenario are the managers of three IT service teams. They are all in their 30’s or 40’s, have advanced English skills and love to discuss a wide range of topics.

As with all my classes, I begin with a warm-up to get them settled into the lesson and thinking in English. I ask them each in turn what they did during the past week, etc. Sometimes with this group we don’t make it out of the warm-up conversation to the grammar book because we get into fairly deep conversations. That’s exactly what happened in this case.

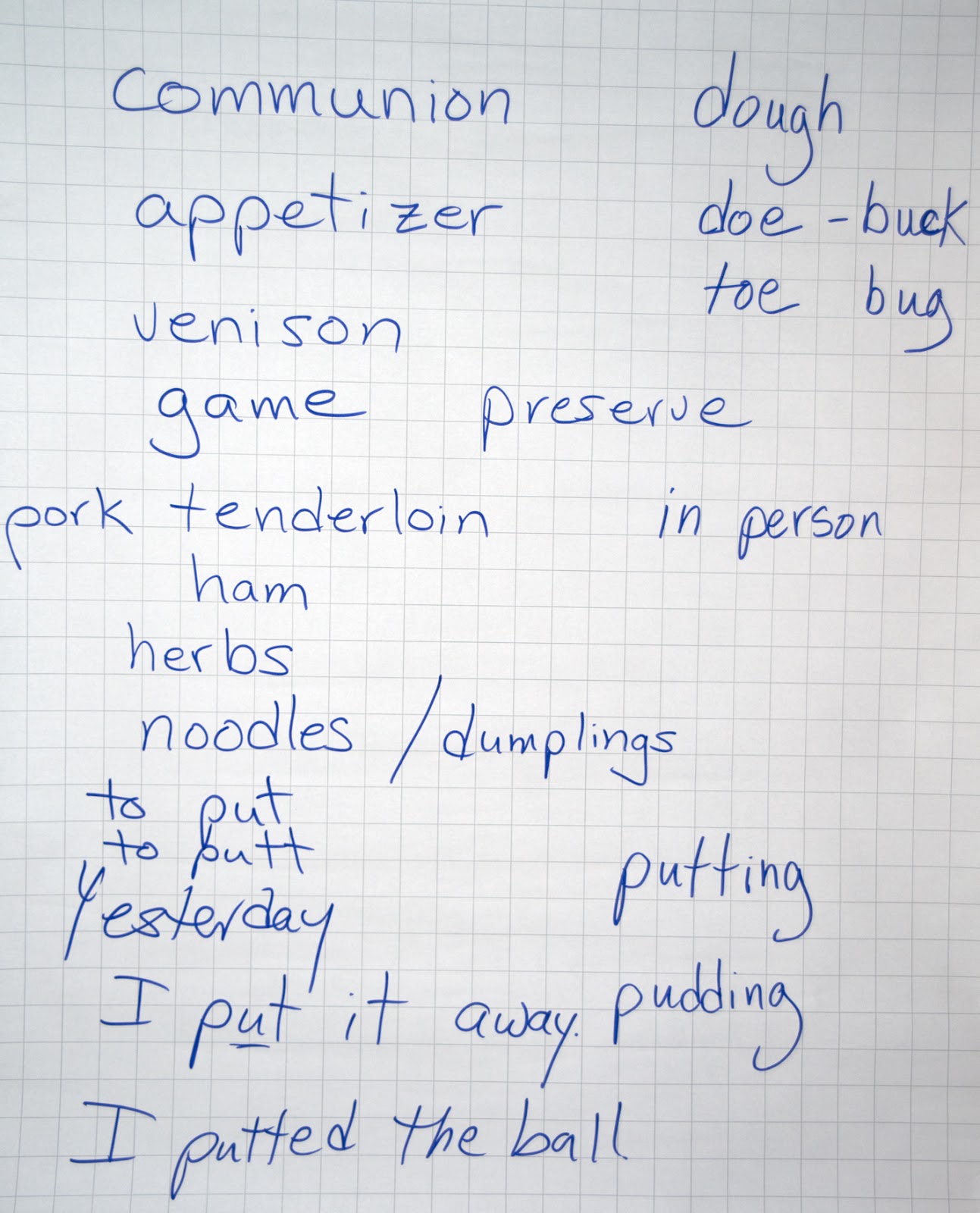

Below is a photo of the flipchart page I used to write new vocabulary for them during this 90-minute session. I’ll try to take you through the conversation we had based on this paper. So refer back to it when you need to.

As you can see, one of the students mentioned that he had gone to a nephew’s First Communion (hence the word “communion” I wrote on the flipchart) over the weekend, which is a BIG deal in this neck of the woods. In the process of telling me what they served at the party at the restaurant, the words “appetizer” and “venison” came up.

Then I explained that venison and other wild animals were called “game” when you eat them, which led to questions about the other meanings of “game,” such as in Monopoly or cards. So I added the word “preserve” which they knew from news broadcasts.

Then came the words for more food (“pork tenderloin,” “ham,” “herbs,” “noodles/dumplings”). Then we discussed the difference in pronunciation for the word “herb” in British and American English. British people pronounce the ‘h’ – in America it’s silent.

Now look at the top right-hand corner of the flipchart. When we talked about dumplings, one student asked me the English word for the German Teig, which I happen to know is “dough.” Then I explained that the pronunciation was the same as “doe,” but that the latter means a female deer (refer back to “venison”).

“Isn’t ‘doe’ what’s on the end of your feet?” asked someone. “No, that’s ‘toe’,” I said. Then someone asked what a male deer was called, hence the word “buck” on the flipchart. Someone else said, “I thought ‘buck’ was the little things that crawl on your arm.” After a couple of minutes trying to figure out what she meant, I finally understood. “Oh,” I said, “no, that’s ‘bug’!”

You can see here a good example of the different ways German speakers pronounce English words. D’s and T’s tend to sound alike, as do B’s and P’s.

Then one of the students asked how to pronounce the word “put” correctly. Many non-native speakers, including this student, say it like “putt”, as in golf ball. I have also heard this pronunciation among Americans from the South.

So you can see on the flipchart that I went into the difference between the two pronunciations (“to put” and “to putt”). Then I explained some conjugation of these two verbs, which you can also see here, saying that “put” is the same in the past tense – an irregular verb – but “putt” is regular and the past tense is “putted.”

This led to the progressive form, which is “putting” for both verbs, but the pronunciation is different. As in, “He was putting the groceries in the cabinet yesterday,” or “Tiger Woods was putting the ball on the 18th hole.”

So check out the word “pudding” under the word “putting” on the flipchart. I wrote that because one of the students said they thought “putting” was the custard-like dessert. So there was THAT explanation!

I enjoyed that lesson so much and felt a little guilty about not getting to the grammar textbook. However, all three students voluntarily told me they thought it was one of our better lessons!

I absolutely LOVE this stuff! And each person has a different take on English depending on their native language. In addition, it helps to modify my teaching methods depending on the original language as much as I can. In this post are examples of German speakers learning English. Don’t even get me started on native Spanish speakers and their pronunciation of “beach” (sounds like “bitch”) and “chair” (sounds like “share”), for just two examples.

Then I have a student who is from Cuba and has learned German, so she mixes all three languages together. And I have a student from Rwanda who speaks Rwandan and French natively. Some days I just don’t know how anyone learns any other language. But somehow we all manage to communicate with each other and have a good time doing it.

On top of everything else, teachers have to tailor their level of English to their students. Therefore, if you have total beginners, you must be careful to speak very slowly and simply. Remember to teach them how to say, “Can you please repeat that more slowly?” during the first lesson!

This is all very taxing. A fellow English teacher made an astute observation to me a few years ago when I was teaching English in the Czech Republic: “Sometimes at the end of the day you hear yourself speaking English exactly like your students.”

If I had to give one piece of advice to anyone teaching ESL, it would be to take a sincere interest in your students’ native languages and cultures. If you demonstrate curiosity about their language and culture, they respond so much better to trying to learn yours.

Here’s to better communication all over the world! Have a great week!

Photo for No Apparent Reason: